- Call Us Today!

- 215-275-7430

Language Matters: Promoting Equality Through Words

In a recent endeavor, I edited a guide to inclusive language for a networking organization striving to diversify its membership. During this process, I encountered a section on “legacy language” and was struck by the inherent sexism in many commonly used terms. Words like “manpower” imply that only men contribute, while “chairman” suggests that only men can lead. Terms such as policeman, fireman, mailman, businessman, foreman, and even mankind perpetuate the notion that men are the default and central to these roles.

This issue extends to language traditionally used for women, such as stewardess, actress, and waitress, which pigeonhole women into stereotypical roles. Gendered terms have been ingrained in societal norms since our country’s inception. The Declaration of Independence, for instance, uses variations of the word “man” six times, entirely excluding women and nonbinary individuals, the latter of whom the founders likely never even considered.

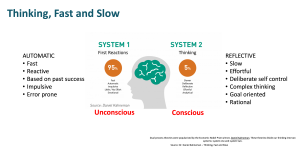

The prevalence of these gendered terms can be attributed to unconscious bias – biases formed through societal messages and experiences over our lifetimes. However, just because these biases are ingrained doesn’t mean we should perpetuate them.

The late Nobel Prize winner and economist Daniel Kahneman identified two systems in the human mind: System 1 and System 2. System 1 operates automatically and quickly, allowing our stereotypes and past experiences to create automatic associations and judgments. Unconscious biases often reside in System 1. Conversely, System 2 is slower and more deliberate. By engaging System 2, we can consciously evaluate our language choices and adopt more inclusive terms.

Instead of saying “manpower,” we can say “workforce.” We can use “chair” or “chairperson” in place of “chairman,” “police officer” instead of “policeman,” “firefighter” rather than “fireman,” “humanity” instead of “mankind,” “server” instead of “waitress,” and “actor” for anyone in the performing arts, regardless of gender.

When we hear others using exclusive language, we should approach them with empathy, assuming they did not intend to offend and would appreciate learning a more inclusive way. Instead of calling them out, we can call them in, explaining how their language may exclude or offend others. By doing so with understanding and compassion, we can work collectively towards removing gender and other biases from our language.

The path to inclusive communication requires us all to be mindful of the words we choose. Together, we can foster a more inclusive and respectful environment for everyone.

The use of inclusive language extends beyond gender to race and ethnicity, pronouns, sexuality, and disabilities. If you’d like to further explore inclusive language, drop me a note: Pat Schaeffer. I’d be delighted to share what I’ve learned.